It is not necessary to know anything about my framework to read any post on this blog. The following page is for anyone who wants to know a bit about my theoretical framework. I am not making an argument here, I am not citing every single person I draw from, and I am not trying to convince another person. Just making some comments on posthumanism and also defining a few slippery terms so that if I use them later, you’ll know what I am talking about. Keep in mind this is a tired busy grad student’s lazy gloss. I am not going into more detail because 1) it’s not that relevant this isn’t a fucking dissertation 2) not to turn off anyone or pre-prejudice a reader since I do think there are issues in politics we can agree on or debate productively without getting Into It.

But this blog used to be called “techtheory” and “theorytech” for a reason. I think it says a lot about how I approach my content that all three of the blog’s names accurately describe how I think about these subjects/

This page is very much a work in progress. There is no point in which that will not be true.

The Low Down:

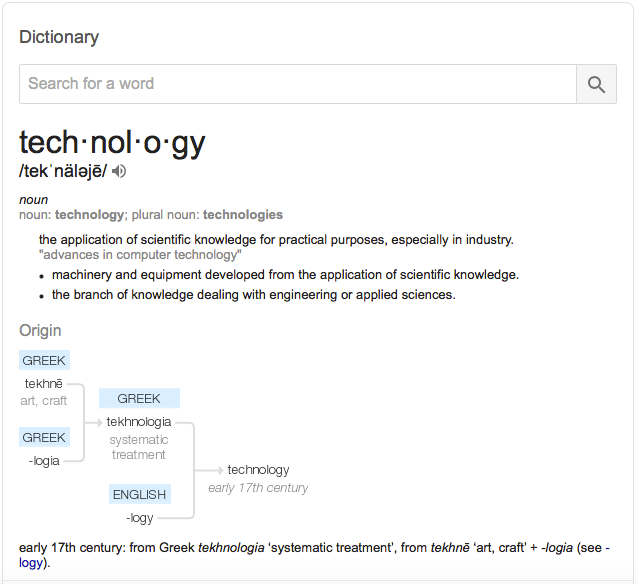

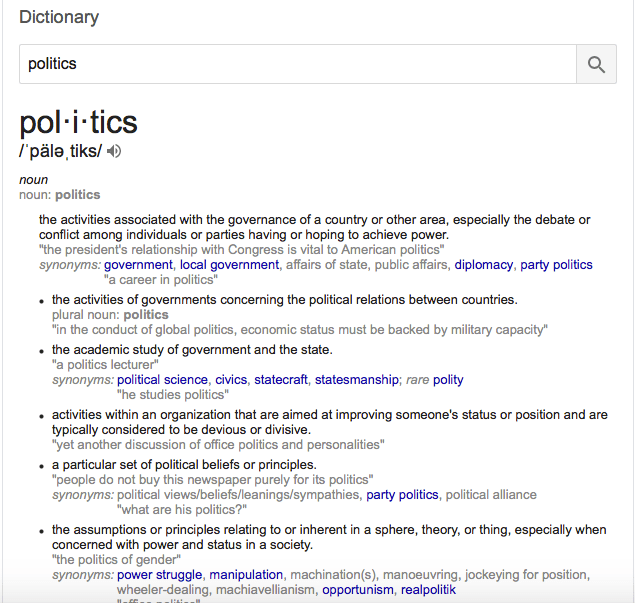

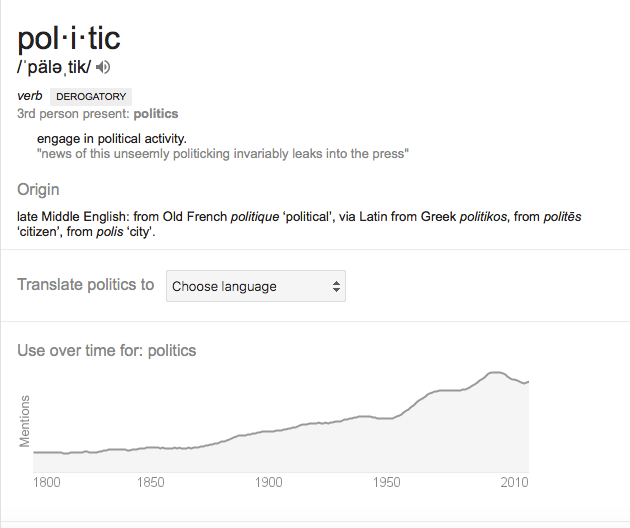

The name “PoliTech” is obviously a shameless “dad pun” from two things this blog was created to discuss together: “politics” and “technology.” But it’s a polymorphously inverse pun, one meant to highlight not only the complexity of the relationship between “politics” and “technology,” also draw attention to how our notions of and connotations around both of these terms mutate and co-evolve in ways that cannot be constrained by dictionary definitions.

The fact is, that notion of “what politics is” and “what technology is” have been defined with and against each other for millennia, sometimes paradoxically.

To put that another way, it is not only that technological innovation changed the way the polis was organized and run. It is not only that politics, in its broadest definition, can instigate technological innovation, especially in the context of national or global communication or in war. Both of these statements are true, but it is also the case that these mutually constituting, mutually deconstructing notions of technology and politics have grown past their Greek roots techne and polis to mutate and co-evolve together in a network of other many related concepts. Related concepts include the evolving definitions of what makes a “human,” as well as abstractions such as “”autonomy,” “capacity to experience beauty and terror,” “morality,” “reason,” and “masturbation.”

The relationship between technology and “society” has repeatedly sparked historically specific, but echoing questions and anxieties.

Examples:

- What is the role of technologies in human society/politics?

- What threats do they pose? What possibilities?

- Are certain relationships between technology and politics inherently “bad”? Or are they inherently neutral, but can be used in bad ways? (I.e., the argument that algorithms are inherently corruptive towards democracy versus the argument well they aren’t inherently but there are many tweaks we need to consider).

- Hell, if we can ask “what is technology,” what does it mean to be human?

- Why are humans different?

- What quality do we have that machines and animals don’t?

- Is it a single set of qualities, or are the qualities that separate us from machines versus the ones that separate us from animals such different qualities that there isn’t a single or set of single qualities shared by all of us or only us?

- In other words, is there a definable stable limit specific to humans alone and the rest of the world or is it that…

- If it turns out that human exceptionalism — the idea that humans are unique and above all animate and non animate beings — is a myth, what does this mean for how we see society and culture?

- Putting aside human/nonhuman identity, what does our idea of “what counts as technology” mean for how we see other cultures?

- By what basis is another culture not “technologically advanced?”

- What does our idea of “what counts as technology” mean for how we think of nations and globalization?

These intertwined concerns have an intellectual history in the West that threads from Aristotle’s writing on slavery through medieval Jesuits and their automaton through the Enlightenment through Frankenstein through Thomas Jefferson and The Manifest Destiny through Kant through Freud through Heidegger through LaTour to that guy on Reddit who is obsessed with the Singularity.

Nor are such concerns restricted to what we have called “The West.” Echoing discourses in other continents, legacies that are perhaps not parallel to the West but certainly adjacent approach such questions in their own contexts that can not be separated from legacies of colonialism and diaspora any more than white Westerners can not honestly separate our technological history from these histories either.

The history of technology is also an intellectual history in which certain tools have not been considered technologies by colonizers who did not consider these technologists fully human. For example, rhetorical devices such as smoke signals used by many Native American tribes were/are both a technological device, performative practice of using it, and as a rhetorical tool for nuanced communication — one of the most incorporated uses of multiple concepts of techne.

It is an intellectual history in which enslaved Black people in the United States contributed by showing (and often subverting) biopolitical subjectivity construction through the surveillance of whiteness that enacted surveillance and the spectacle well. Such biopolitcal practices existed and were established well before and beyond the intellectual framework of panopticonism miscredited to Michel Foucault (see Simone Browne Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness).

In short, the history of technology is a history of humanity. Who is visible. Who is a subject. What is “technology” and why is linked to who is “human” and “why.” Such questions span from Aristotle’s consideration of the hierarchy of beings and consciousness that equivocated slaves with “techne” (same word for tools) to Karl Marx (who was surprisingly influenced by Aristotle)’s critique that the worker had become a tool or cog in the capitalist machine in ways that denied their existential essential human nature.

Personally, I am less concerned with establishing a “human nature” than exploring the consequences of where and how this limit was established. I am not particularly caught up on the limit or limitrophy of the human. The more I learn about technological relations the more I am convinced that there can be no line drawn, whether in the context of Katherine Hayles’ notion of technogenesis or notions that use of techology is what makes us “human”…though it is not an exclusively human trait…which brings us back to technology. However, I would go even further than that.

But to keep it short and sweet here, I suppose I could be called a post humanist and I have called myself that before to idencate a general ideological allegiance. More precisely, I tend to think of my worldview as aligned more closely with extrahumanism. Extrahumanism tends to frame humans, animate and non-animate environs, technology, and the milieu in which we “gell” as so entwined that those “limitrophies” of the human can’t be established. There is a nitpicky distinction between “posthuman” and “extra human.” Some post humanists define the term as a belief we are/will evolve beyond the species “human” as we currently define it. Some people simply mean a worldview that is “post” the humanist worldview. Some people define it other ways. Extrahuman implies we are — sorry guys for the phrase– always already not human as we define it. This concept in much scholarship in my field is actually not linked to LaTour, though many people in STS (science and technology studies) are.

That debate is not really relevant here. I’m just clarifying my stance because “posthumanism” is such a slippery word, like postmodernism, that I wanted to make it clear what I was talking about.

What About Ethics Though?

In Echographies of Television, Jacques Derrida writes that the inability to pin down stable definitions of concepts such as “democracy,” “the nation,” or “the border” does not relieve us of the infinite responsible to address the consequences of these flexible notions. In a book in which Derrida discusses xenophobia, anti-semitism, and revisionist history in France as much as he discusses media theory, Derrida ends his passionate rejection of Le Pen’s anti-immigration polices by admitting that the entire concept of the state and democracy is flawed (I am waaaaaay oversimplifying here). But, he writes,

“To acknowledge this permeability, this combinatory and its complicities, is not to take an apolitical position, nor is it to pronounce the end of the distinction between left and right or the “end of ideologies.” On the contrary, it is to appeal to our duty to courageously formulate and thematize this terrible combinatory…to another delimitation of the socius–specifically, in relation to citizenship and to the nation state in nation, and more broadly, to identity…It is hardly possible to talk about all this in an interview and in parentheses. And yet…these problems are anything but abstract or speculative today (19-20)

Translation: nothing is pure or perfect, no system, no democracy. You can’t “pin down” a stable concept. But although everything deconstructs itself/can be deconstructed this doesn’t affect everyone equally. The changing construction of “the border” or “French national identity” materially affects immigrants more than French citizens. So even though everything is fucking complex and I write in a way that seems to make it more complex, because these conditions affect real people, you don’t get to throw your hands up like “the right and the left are both corrupt! No one has a stable ideology!” because that’s lazy and wrong when real life immigrants in France will be hurt. So get off your ass and vote and protest LePen anyway because Derridean ethics* are all about accepting our world is a deconstruction cluster-fuck but that doesn’t mean we aren’t responsible to how we treat other beings!”

This is a side of Derrida that is not often discussed. What interests me most about this passage (aside from how eerily applicable that something written in 2002 is to 2018) is the idea that flux of being, a constantly deconstructed/ing world, does not mean you get to be a dick about it. Derridean ethics and his concept of responsibility are an entirely different conversation and to be clear I’m not a hardcore Derridean (though I do think his ideas are often misunderstood and I do try to present him on his own terms out of fairness).

What interests me here is the concept that the posthuman is not the post political.

As a posthumanist, or rather, an extrahumanist, I am not particularly caught up on the limit or limitrophy of the human. I do not think any hardcore humanists or those of other philosophical persuasions should be bothered by this standpoint reading this blog since it does not come up often. I am caught up on a history in which these delineations have very, very real material consequences.

Just because I do not believe there is a single quality delineating humans from other forms of existence (jesus that’s going to be a hell of a dissertation chapter) does not mean I am indifferent to the violence inflicted upon beings because of who is allowed to be human.

I approach technology as a fluid and flexible term and therefore write about some things on this blog that may not “look” like technology to some people.

I do not frame my research on technology with the question “does technology change something fundamental about what it means to human?” because I do not believe there is a fundamental essence or “soul” to humanity. I do not find the idea of AI eventually meeting some abstract standard to which a nation can assign AI citizenship to be inherently alarming. It is a pointless question to me.

The effects are not pointless. “Does technology make people more lonely?” is a question I would turn to social scientists to answer. Is it possible that drones that the U.S. uses in Syria and Afghanistan advance to the point where they begin algorithmically calculating the “acceptable likelihood” of killing innocent civilizations differently than how drone algorithms calculate “acceptable likelihood” now (Calo “Robotics and the New Cyberlaw”) is a question for someone who knows far more about drones than me. But the question underlying each of these raises questions about how are we to live and who is acceptable to die.

On a more abstract level, when we say “Facebook is responsible for misinformation on its site” are we talking about a digital platform or people? And by “responsible,” do we mean it in the forward-sense of “ethically required to change” (Aristotelian political rhetoric) or responsible in the backward looking sense of “responsible in the sense of guilt” (Aristotelian political rhetoric). In a world where corporations are people and unproductive squabbling over “who is responsible for social media misinformation? Bots or humans?” (okay that last one really gives me a headache because people talking about bots like they aren’t programmed by humans drive me crazy while talking about humans like our brains are “programmed” to react to certain stimuli, including bots, is equally wrong but that concept simply did not occur to me until I researched it).

We cannot throw our hands up and say “the government did it” or “the Tech Industry(tm)” did it because the interactions between humans and technology are so close that assigning “responsibility” is a deeper ethical conundrum than most people realize. The task is to learn how to live and to live well in the clusterfuck.

Further Reading:

NOTE: I usually try to share open sources only or mostly. However I am a very busy graduate student and tbh it is easier on me to lay out parts of The Syllabus on posthumanism/extrahumanism. I will update slowly over the future.

Also there should be a hella more, like, Deleuze or something. And I know this “list” is waaaaay on the humanities side of the list (even though a lot of this was written by former or current software programmers like Frabetti but they’re still making “philosophical” conclusions so). I’m too lazy to hunt down more. Again, I will update this slowly because it takes A LOT of work to track this shit down.

Message me if there is a piece you really want and I’ll see what I can do.

Boyle, Casey. Rhetoric as a Posthuman Practice. The Ohio State University Press, 2018.

Brown, Jim. Ethical Programs. University of Michigan Press, 2015.

Brown, Jim. “the machine therefore I am.” Philosophy and Rhetoric vol. 47, no. 4, Extrahuman Rhetorical Relations: Addressing the Animal, the Object, the Dead, and the Divine, 2014, pp. 494-514.

Davis, Diane. “Afterwords: Some Reflections on the Limit.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 47, no. 3, 2018. pp. 275-284.

Davis, Diane. “Autozoography: Notes Toward a Rhetoricity of the Living.” Philosophy and Rhetoric vol. 47, no, 4, 2014. pp 532-352.

Frabetti, Federica. Software Theory:A Cultural and Philosophical Study. Rowman and Littlefield, 2015.

Geiger, R. Stuart. ‘‘Bots, Bespoke, Code and the Materiality of Software Platforms.’’ Information, Communication & Society, vol. 17, no. 3, 2014. pp 342-356.

Haraway, Donna. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Haraway, Donna. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Towards a Politics of Sexuality.” Feminist Theory: A Reader, edited by Frances Bartkowski and Wendy K. Kolmar, 2010, pp.336-354.

Hayles, N. Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics. University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Hayles, N. Katherine. How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Mackenzie, Adrian. Transductions: Bodies and Machines. Bloomsbury, 2002.

Mager, Astrid. ‘‘Algorithmic Ideology.’’ Information, Communication and Society, vol. 15, no. 5, 2012, pp 769-787.

Maher, Jennifer. “Artificial Rhetorical Agents and the Computing of Phronesis.” Computational Culture, vol. 5, 2016. Accessed: Sept 6 2018.

Marder, Elissa. Pandora’s Fireworks; or, Questions Concerning Femininity, Technology, and the Limits of the Human.” Philosophy & Rhetoric, Vol. 47, No. 4, EXTRAHUMAN RHETORICAL RELATIONS: Addressing the Animal, the Object, the Dead, and the Divine (2014), pp. 386-399

Pfister, Damien Smith.“Against the Droid’s “Instrument of Efficiency: For Animalizing Technologies in a Posthumanist Spirit.” Philosophy & Rhetoric, vol. 50, vo. 2, 2017, pp. 201-227.

Pruchnic, Jeff. Rhetoric and Ethics in the Cybernetic Age: The Transhuman Condition. Routledge, 2014.

Simondon, Gilbert. “The Position of the Problem of Ontogenesis.” Parrhesia, no. 7, 2009, pp. 4-16.

Winner, Langdon. Autonomous Technology: Technics-out-of-Control as a Theme in Political Thought. MIT Press, 1992. REALLY GOOD HISTORICAL BACKGROUND.

Zemlicka, Kurt. “ The Rhetoric of Enhancing the Human: Examining the Tropes of ‘the Human’ and ‘Dignity’ in Contemporary Bioethical Debates over Enhancement Technologies.” Philosophy and Rhetoric, vol. 46, no. 3, 2013, pp. 257–279.

Works Cited:

Calo, Ryan. ‘‘Robotics and the New Cyberlaw.’’ California Law Review, no. 103, vol.4, 2015, pp 101-46.