So why do I see some political ads on my Facebook feed and not others? What information does Facebook give to third party platforms that influences what I see, and how do I know? How did Russian misinformation factor into this? And hell, what even is a “political ad” anyway?

The holidays are over, which means that soon the presence of advertisements in our lives should be winding down from “pre- and post- Xmas deluge” to the usual “saturated ambience.” The 2018 midterms are also over — long over, in news cycle time. But that doesn’t mean that political advertisements are gone. Unlike their commercial counterparts, some political ads work best by keeping sneaky and subduing the “pitch” they’re selling, and the difficulty in distinguishing some political ads from “news” or “information” has baffled both individual users and Facebook.

This blog post cannot exhaustively cover what political ads are, or how Facebook fucks up deals with them. Instead, I am simply going over three simple, open-source resources for you to check out how political advertisements on Facebook are identified and how they work to target audiences and convey (mis?)information: the Facebook Ad Archive, ProPublica’s Political Ad Collector, and The Internet Research Agency Project.

I can’t offer any insight into whatever the hell was going on with Tumblr’s ads.

…but I hope that these resources empower you to begin investigating the political ads that influence our role in online and offline civic activity.

Political Advertising

Let’s start with a brief overview of the controversial definitions of political advertising. Well, the definitions vary by country. In Australia, for example, “Political advertising is advertising that attempts to influence or comment upon a matter which is currently the subject of extensive political debate [AdStandards].” It does not need to be paid for or in service of a particular candidate or party and does “not necessarily include all advertising by governments and organisiations…involved in the political process, such as lobby groups or interest groups” or advertising that “may be regarded as informational or educational rather than political…as determined on a case-by-case basis (Political and election advertising, AdStandards.”

Facebook’s regulations for political advertising in the U.S. is far more strict as of December 2018, even while the FEC struggles to craft new rules in the digital age. Facebook’s current definition of a “political advertisement” is one that

- “Is made by, on behalf of, or about a current or former candidate for public office, a political party, a political action committee, or advocates for the outcome of an election to public office; or

- Relates to any election, referendum, or ballot initiative, including “get out the vote” or election information campaigns; or

- Relates to any national legislative issue of public importance in any place where the ad is being run; or

- Is regulated as political advertising (Facebook Business, “About ads related to politics of issues of national importance”).

Facebook’s list of“ issues of national importance “ (“Issues of national importance”) are: abortion, budget, civil rights, crime, economy, education, energy, environment, foreign policy, government reform, guns, health, immigration, infrastructure, military, poverty, social security, taxes, terrorism, and values.

If an ad meets these criteria, then it “require[s] advertiser authorization and labeling for ads targeting the US.” These ads are reviewed by Facebook “before they’re shown on Facebook through a combination of artificial intelligence (AI) and human review” to make sure they meet “community standards.”

Which brings us to the Facebook fiasco that gave us The Facebook Ad Archive.

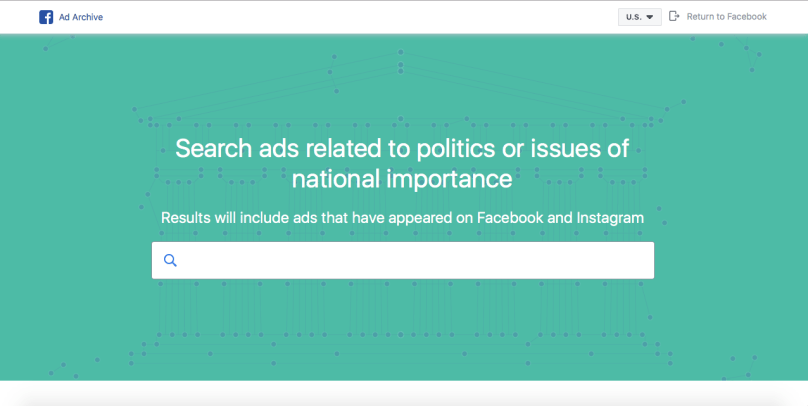

The Facebook Ad Archive

After coming under fire for letting misinformation amok in 2016, Facebook and Instagram declared in summer 2017 that they would “label” potential misinformation and political ads and to archive political ads online in order to curb misinformation spread (Techcrunch). They also made plans to archive political ads online, and “in the interest of transparency” changed their ad acceptance criteria to require that

- “Ads related to politics or issues of national importance that appear on Facebook or Instagram should include a disclaimer provided by advertisers that shows the name of the person or entity that paid for the ad.

- Ads related to politics or issues of national importance may be stored in the Ad Archive for a period of up to 7 years. For country-specific information on how ads will appear in the Ad Archive, please review the information for your country below.”

The idea behind flagging was that if people knew that a paid message on their dash was a political ad, then they would be less likely to take its statements at face value. If people could “look up” an ad in Facebook’s archive, they could identify how they may have been mislead in the past.

This plan backfired like a shotgun. For one thing, Facebook’s screening algorithms kept tagging news instead of ads (ProPublica) (see previous entry on Tumblr’s similar but far more lazy attempt to police porn). Facebook also failed to eliminate hate speech, pissed off publishers, and had other issues related to the company. On top of that, because fake news spreads faster than “real news,” and flagging had either minimal impact or made everything worse. The whole thing was such a disaster that Facebook abandoned it in December 2017.

However, the Facebook Ad Archive still exists. And, for now, still states that it will archive all identified political ads on Facebook (constantly updating) for seven years after the ad’s publication…but only seven years.

Since Facebook, a cooperation attempting to clear up potential misinformation, created this ad archive in a gesture of transparency, one would expect the archive to be neatly tagged and organized. After the “flagging” disaster, we would especially expect a more clear delineation between between “legit” ads and misinformation. Especially since Facebook is such a beacon of transparency, an inspiration for organizing its content in ways easily accessible (in multiple meanings of the word) to the public….

Okay, I’ll spare you the Michael Blum with the dove gif and get on with it.

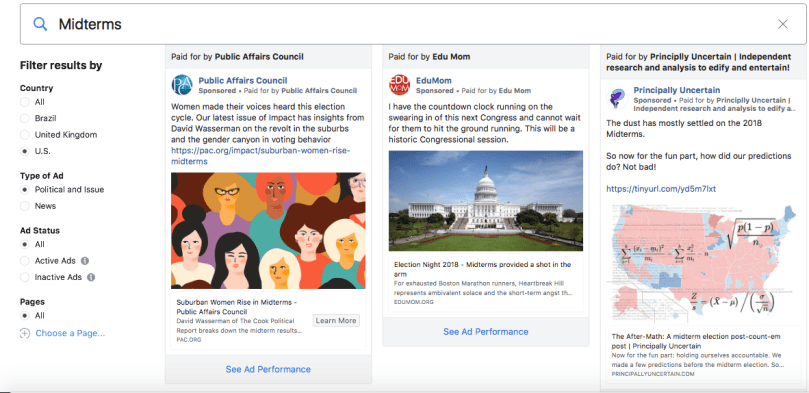

Once you search a term — let’s go with “Midterms” — you will be taken to this interface.

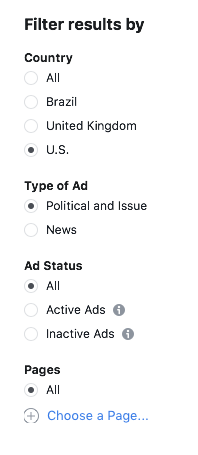

On the “Filter Results” sidebar, you can filter results by country (U.S., U.K., Brazil), “type of ad” (political and issue, news), and ad status (active, inactive, or all).

You can also search by the Facebook Pages promoting ads.

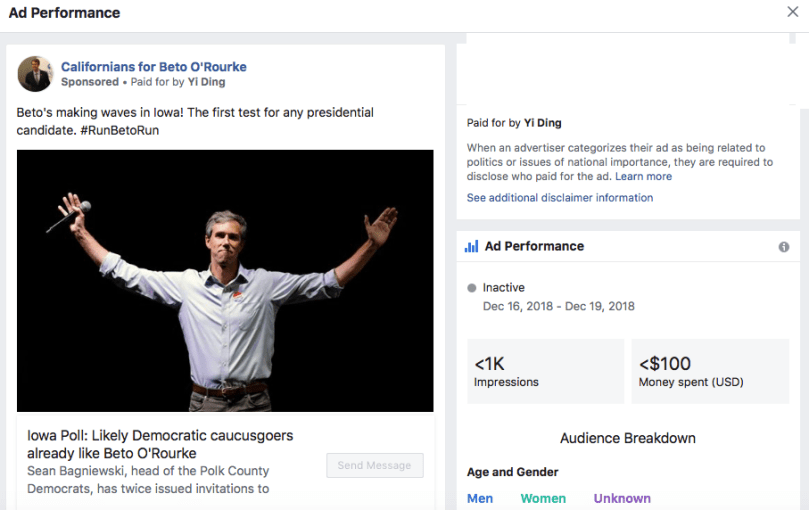

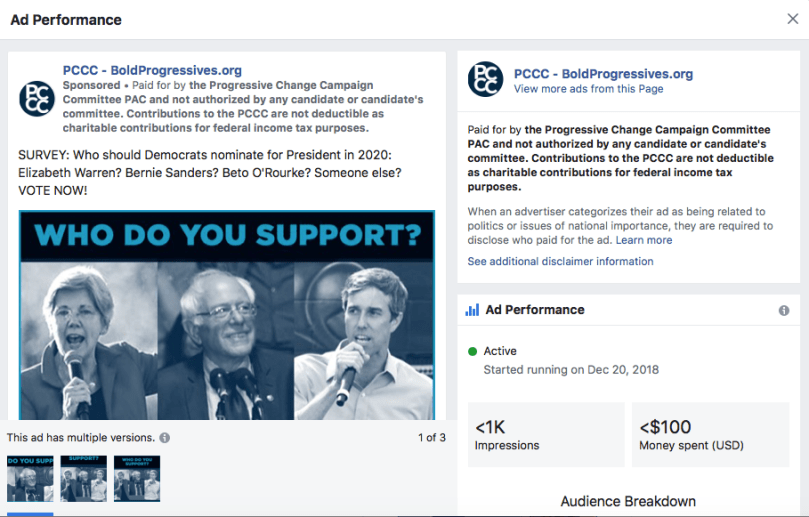

Keep in mind that the Facebook page sponsoring an ad is not always the person who pays.

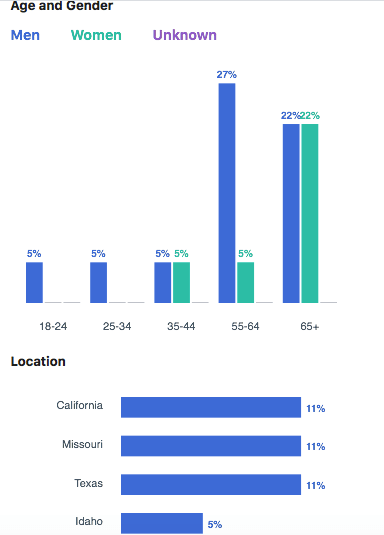

Clicking on “Ad Performance” at the bottom of an ad shows how many impressions were made, the demographics, and location along with (very broad) cost brackets.

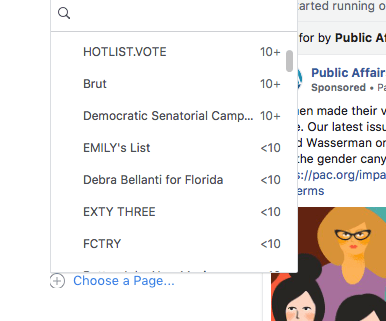

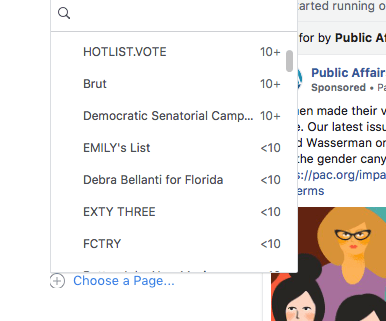

The most prominent potential design issue with the site that leaps to my mind is the Page Filter. Although the alleged purpose of the archive as an anti-misinformation tool, the ability to search by page does not give insight into credibility.

To go back to this image.

You would have to already know who these people are coming into the search for this to be useful. In other words, none of this gives insight into the credibility of the source. Most people — including me — are not going to look up every individual source (I mean I looked up Bellanti for the purpose of this post and this seems like, legit, her campaign for Florida state senate, I already knew that EMILY’s list is a pro-choice foundation, and didn’t care enough to look up the rest). However, the page filter IS useful if you are researching all ads paid for by a single entity, say, Southern Poverty Law Center or one of the PACs pupper-funded by the Koch brothers.

The other main issue is the News vs Political or Issue delineation which delves into philosophical questions beyond the scope of this post.

While the Facebook Ad Archive is a start in the right direction, one thing the archive has no intention of showing does not show is how these ads affect your individual experience on Facebook. Going back to a previous post on filter bubbles on this blog and personalization, what factors of “personalization” contribute to what kinds of ads I do or do not see on my Facebook feed? In other words, what information does Facebook give to third parties and how does it make me more likely to see some political ads and not others?

ProPublica’s Facebook Political Ad Collector

Critical of Facebook’s move to make their archive public, writing that despite FB’s publicity ploy to display more “transparency,” the nonpartisan, independent, investigative journalism hub ProPublica pointed out that the Facebook’s requirement that ads divulge their sources does not equal transparency for how these ads target different audiences (which was arguably the whole point of the archive as an anti-misinformation tool).

“If the policy works as Facebook hopes, users will learn who has paid for the ads they see. But the company is not revealing details about the significant aspect of how political advertisers use its platform — the specific attributes the ad buyers used to target a particular person for an ad (Merril et. al., What Facebook’s New Political Ad System Misses).”

Thus, ProPublica introduced The ProPublica Political Ad Collector: a data-scraping and analysis tool that estimates your personal niche in an algorithmically-sorted set of audiences based on demographic information and user personalization.

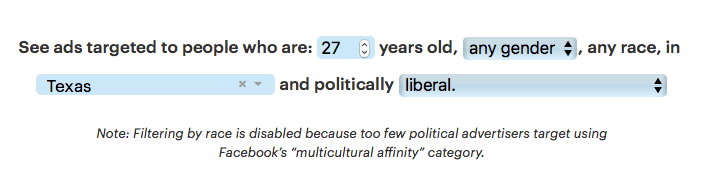

To use the tool, start by inserting your age, city and/or state, one of three choices under political ideology, and what gender (if any) you want to see ads targeted for.

Then, the tool calculates and gathers together ads aimed at your demographic niche.

Then, the tool calculates and gathers together ads aimed at your demographic niche.

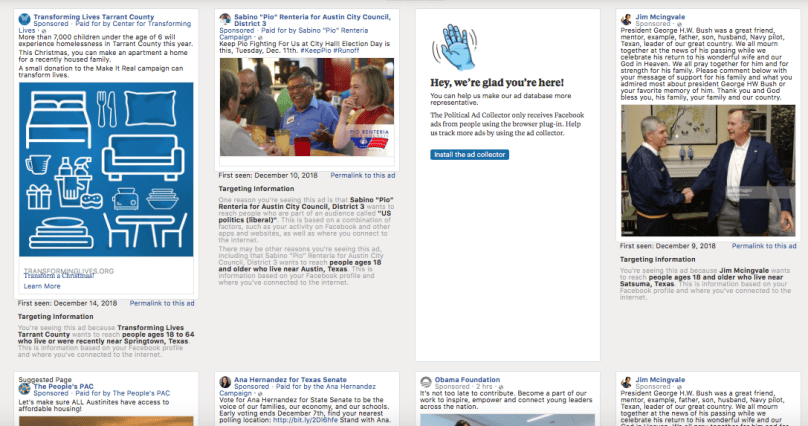

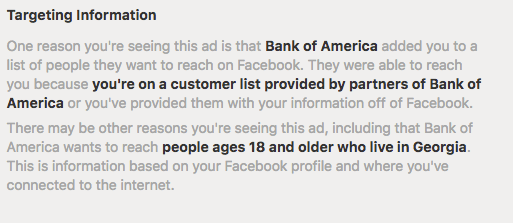

The gray box below the ad provides information on why you were selected as an audience.

What the Political Ad Collector shows is

- how personalization goes into advertising and target audience.

- the ways that advertisements cater not only to demographics, but also to political identification

- But not the same identifications in the same way at each time (in fact, the trend that the right tends to be more extreme and concentrated appears here as well)

The ProPublica tool is not perfect. But it offers some insight into why some people are targeted instead of others, and what personal information Facebook gives out to third parties for them to calculate what content you, individually, see on your dashboard.

Internet Research Agency Ads

Finally, we’re going to dive in to some of the ads that were identified as Russian propaganda by the Internet Research Agency Project, an initiative undertaken at The Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities, designed by Drs. Damien Smith Pfister, Nora Murphy, Meridith Styer, and Misti Yang in collaboration with Purdom Lindblad and Ed Summers, for undergraduate students in the University of Maryland’s “Interpreting Strategic Discourse” to learn how to code by hand the database needed for us to explore “the rhetoric of computational propaganda that occurred on Facebook during the 2016 election {x}” The goal was to create an ongoing database to archive ads that have been tied back to the Russian “troll farm” and propaganda factory, the Internet Research Agency.

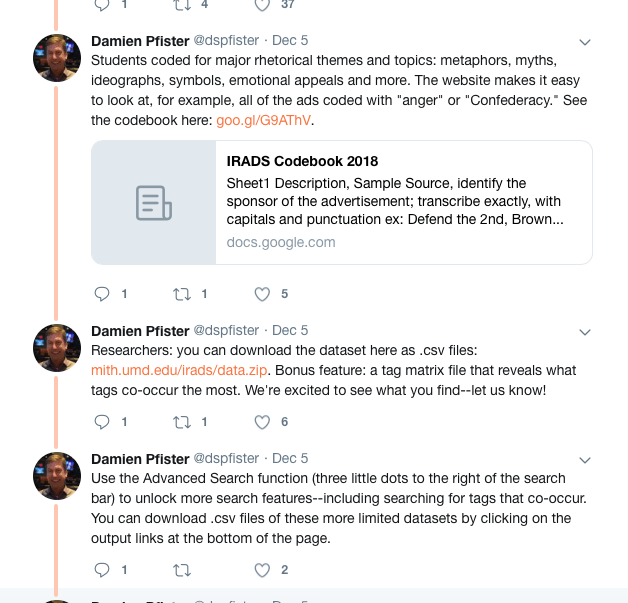

On December 5, 2018, Pfister, a communication professor and rhetoric scholar (whom I have cited on this blog before x) shared on Twitter:

(I cannot emphasize enough how cool it is that he and his colleagues received permission from the University of Maryland to make this a free, open-access database).

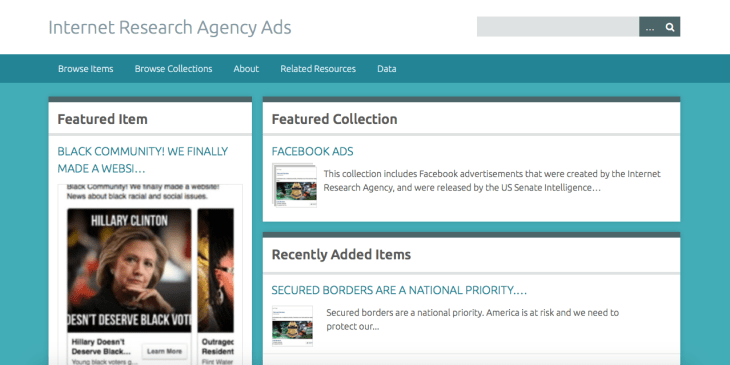

Pfister even gave you a summary and tutorial on how to use it so I don’t have to! Even if he had not, the interface is fairly self-explanatory — a very simple page with a large, visible search bar at the top right hand corner of the screen. The header bar under the title is also self-explanatory.

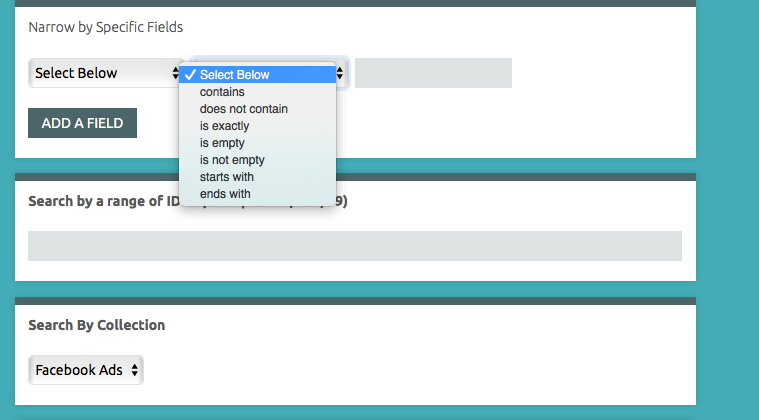

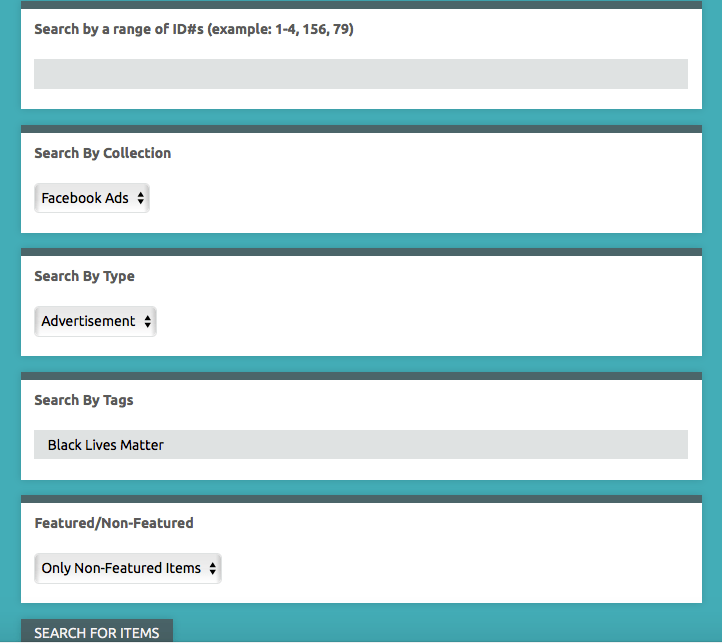

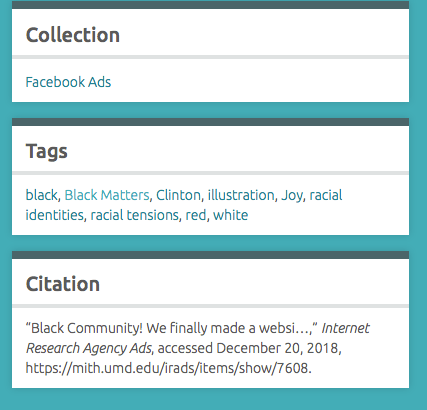

You can “Browse Items” by searching for a keyword. To refine your search, you can filter by the (impressively detailed and numerous) fields

As well as by categories listed below. Right now, the “Facebook Ads” collection is the only organized collection, though this should change as the database continues to develop.

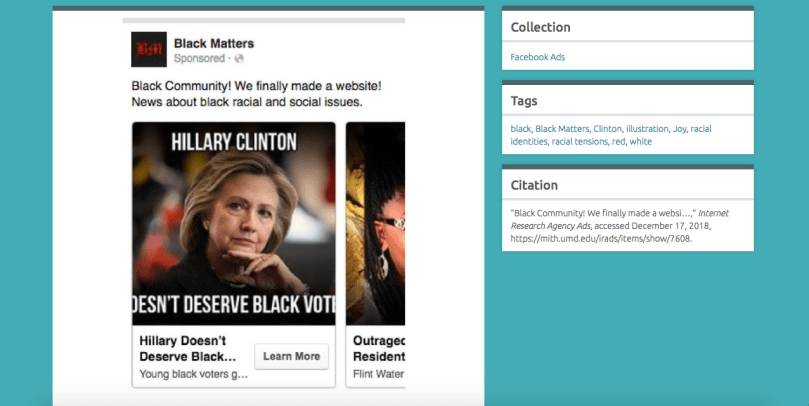

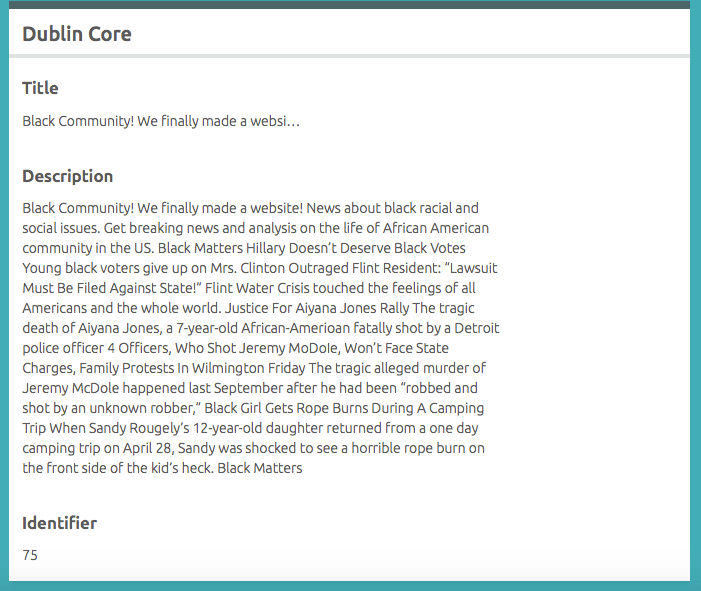

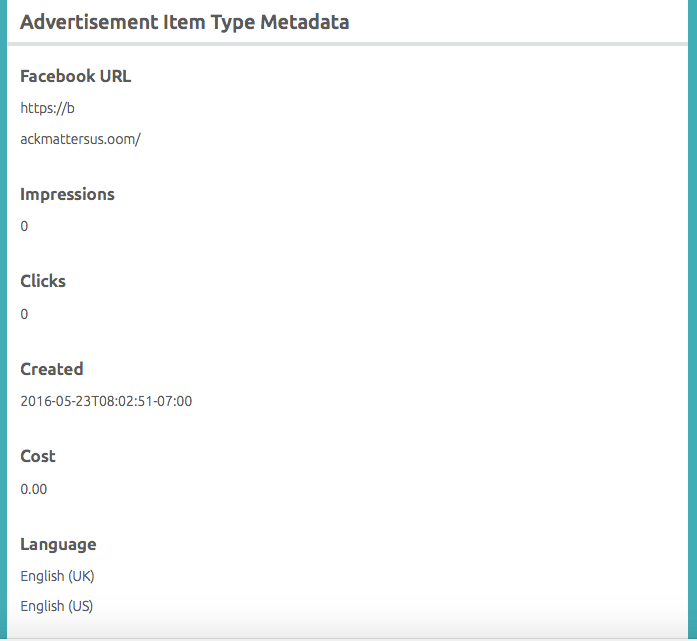

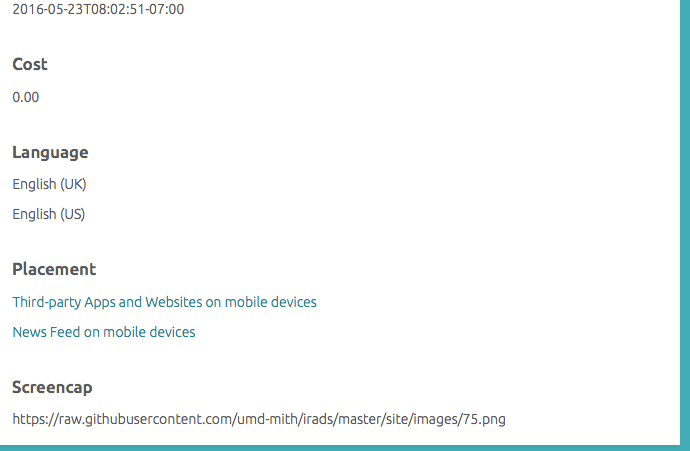

If you click on an item, you can see this metadata information as well as a formatted citation.

This ad was created for free and did not get any impressions or clicks. This does not mean it does not have critical value as a cultural object — for every post that goes viral, there are many similar attempts. Contrast however with this post for “Unapologetically melaneted Kings and Queens” which cost the IRA $918.64 in Rubbles (and oooooh yeah, that is not the last time I am mentioning that particular ad on this blog again (“melaneted?”)),but right now I’m just gonna leave it at damn y’all paid that much money and couldn’t check with a professional English translator?). (In fairness, we white Americans butcher AAVE pretty badly too).

This part also shows where the ad was placed — it seems to have been a mobile specific ad (which may also contribute to lack of clicks). This is extremely important for rhetorical analysis of audience and effectiveness in the context of media theory. Intro to Media Theory is also, definitely, beyond the scope of this post (this post could’ve turned into a 5000 word essay but ain’t nobody got time for that). But while Marshall McLuhan’s adage that “the medium is the message” can be thrown around indiscriminately, the idea that what medium you encounter information (newspaper, billboard, word of mouth, on a cellphone screen, a laptop), including place and environment (the front page of The Enquirer in the grocery store checkout and a cellphone screen have different implications even if you see the same image and text) is part of the information being conveyed. Thus things like position, whether an ad is on your Facebook sidebar or on the news feed, is both a rhetorical choice and also has a rhetoric effect — something Facebook itself recognizes, given that “an ad’s images, text and positioning as well as the content on an ad’s landing page” factors into how Facebook declares an ad to be in violation or agreement with their rules (yet for some weird reason this doesn’t seem to be something worth putting on the Facebook Ad Archive…).

Conclusions:

Although there is much left to say about each of these resources and how much is desired for one of them, I will stop here because it is the day after Christmas for those who celebrate it, and I’m thankful for anyone who sat through what may have been the driest post on this blog so far that was not a software 101 tutorial. I hope that 2019 brings you joy, strength and vigilance, and that, if nothing else, in some small way, I could help spark ideas for ways to productively procrastinate in the upcoming year.

Works Cited

Anonymous. “Sorry to Burst Your Bubble 1/3.” Tech Theory, Published: December 16, 2018. Accessed: December 19, 2018. https://techtheoryblog.com/2018/12/16/sorry-to-burst-your-bubble-1-3/

“Black Community! We finally made a websi…,” Internet Research Agency Ads, accessed December 17, 2018, https://mith.umd.edu/irads/items/show/7608.

Lee, Michelle Ye Hee. “FEC struggles to craft new rules for political ads in the digital space.”The Washington Post, Published:June 28, 2018. Accessed: December 20, 2018.

Levin, Sam. “Facebook promised to tackle fake news. But the evidence shows it’s not working.” The Guardian, Published: May 16, 2017. Accessed: December 18, 2018.

Lohr, Steve. “It’s True: False News Spreads Faster and Wider and Humans Are To Blame.” The New York Times, Published: March 8, 2018. Accessed: October 17, 2018.

Merrill, Jeremy B. and Ariana Tobin. “Facebook’s Screening for Political Ads Nabs News Sites Instead of Politicians.” ProPublica, Published: June 15, 2017. Accessed: January 20, 2018.

Merrill, Jeremy B., Ariana Tobin, and Madeleine Varner. “What Facebook’s New Political Ad System Misses.”ProPublica, Published: May 24, 2017. Accessed: January 20, 2018.

Pfister, Damien Smith. Twitter, Published: December 5, 2018. Accessed: December 5, 2018. https://twitter.com/dspfister/status/1070420973072068611

Sisario, Ben. “Facebook’s New Political Algorithms Increase Tension With Publishers.” The New York Times, Published: June 14, 2018. Accessed: January 20, 2018.

“Unapologetically melaneted Kings and Que…,” Internet Research Agency Ads, accessed December 21, 2018, https://mith.umd.edu/irads/items/show/6466.

Unknown. “Political and Election Advertising.” Ad Standards, Accessed: December 17, 2018. https://adstandards.com.au/products-issues/political-and-election-advertising.

2 comments